One of the things that really separates the current Captain Marvel and Hawkeye ongoings from the rest of Marvel’s current comic crop is the artwork. Names like Emma Rios, Dexter Soy and David Aja are putting best feet forward for those books by veering towards artistry that’s a far cry from the stereophonic colourfest that is most of superhero comics’ main go-to. Rios goes for off-beat pencils, Aja is a stripped-back ‘acoustic’ illustrator, and Soy makes everyone look like Skrulls. Ok, so art off the beaten track doesn’t always work, but at least it’s an attempt at something that breaks the mold a little.

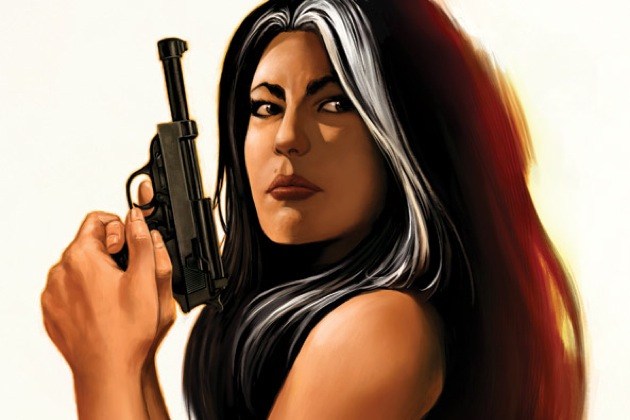

My thoughts on reading the first volume of Nathan Edmondson’s current Black Widow series began and ended with the artwork – namely, that it seemed to be trying a little too hard and wasn’t quite confident in its approach. I wouldn’t normally bring it up this early in the review, but it’s worth noting up front. The Finely Woven Thread is definitely a pretty book, but artist Phil Noto can’t seem to decide whether to go with the barebones approach with minimal colour and heavy emphasis on what’s on the panel rather than how pretty it is – a la Aja – or to stick with the flourishing, gorgeous watercolours (I think?) and sweeping combat layouts that evoke David Mack’s work on Daredevil with Brian Bendis. One part of Thread resembles a beautiful fever dream, the other’s a 60s throwback that could only be complete with giant dots and its protagonist in a go-go dress.

My thoughts on reading the first volume of Nathan Edmondson’s current Black Widow series began and ended with the artwork – namely, that it seemed to be trying a little too hard and wasn’t quite confident in its approach. I wouldn’t normally bring it up this early in the review, but it’s worth noting up front. The Finely Woven Thread is definitely a pretty book, but artist Phil Noto can’t seem to decide whether to go with the barebones approach with minimal colour and heavy emphasis on what’s on the panel rather than how pretty it is – a la Aja – or to stick with the flourishing, gorgeous watercolours (I think?) and sweeping combat layouts that evoke David Mack’s work on Daredevil with Brian Bendis. One part of Thread resembles a beautiful fever dream, the other’s a 60s throwback that could only be complete with giant dots and its protagonist in a go-go dress.

tl;dr – art is pretty, but needs to choose a style and stick with it.

But I guess the switch-footing artwork goes a little hand-in-hand with the story itself, which seems like an attempt at the Marvel Universe as written by John le Carre as it  follows the eponymous Black Widow’s moonlighting as an assassin when she’s not saving the world with SHIELD. Everything up until the halfway point of Thread is a standard job-of-the-week narrative until we start to hit the arc-based stuff when a dude with a very personal grudge against the Widow shows up, literally, as an agent of chaos (seriously, the arc words beginning here are all the do with “chaos”, which gets a little on the nose). From there we get the beginnings of what I imagine is a story with further reach than Edmondson’s originally clued us in to, which is exciting if a little belated.

follows the eponymous Black Widow’s moonlighting as an assassin when she’s not saving the world with SHIELD. Everything up until the halfway point of Thread is a standard job-of-the-week narrative until we start to hit the arc-based stuff when a dude with a very personal grudge against the Widow shows up, literally, as an agent of chaos (seriously, the arc words beginning here are all the do with “chaos”, which gets a little on the nose). From there we get the beginnings of what I imagine is a story with further reach than Edmondson’s originally clued us in to, which is exciting if a little belated.

Thread is a decent book, maybe even an OK book, but I’m left feeling like something’s missing afterwards. Edmondson does a great job bringing the Widow to life as a character and a badass simultaneously, with reason and motivation between the two fuelling each other nicely. The settings are nice, the plot’s streamlined enough for most to follow, and the page layouts during fight scenes are, without hyperbole, the best I’ve seen since Frank Miller’s work on that Wolverine miniseries. Widow’s supporting cast is good, surprisingly bereft of big name Marvel players besides incumbent SHIELD Director Maria Hill and a brief appearance by Hawkeye in a jab at Matt Fraction’s series.

Actually, speaking of Hawkeye, I’m reminded of another thing delineating the successes of Captain Marvel and Hawkeye; the stories are fresh, separate and focus largely on gaps in their respective protagonists’ day jobs. Ok, maybe not so much Captain Marvel, but quite a lot of the stuff in her first volume only featured her traveling in time and fighting during World War II without Avengers backup. The books focus on the characters as people in addition to being superheroes, relying on their particular strengths to hold a narrative on their own without hitting the panic button and calling for Captain America when things get rough.

Actually, speaking of Hawkeye, I’m reminded of another thing delineating the successes of Captain Marvel and Hawkeye; the stories are fresh, separate and focus largely on gaps in their respective protagonists’ day jobs. Ok, maybe not so much Captain Marvel, but quite a lot of the stuff in her first volume only featured her traveling in time and fighting during World War II without Avengers backup. The books focus on the characters as people in addition to being superheroes, relying on their particular strengths to hold a narrative on their own without hitting the panic button and calling for Captain America when things get rough.

This is something Black Widow attempts, but doesn’t quite succeed at. The Widow herself is definitely independent on the job and largely off it too, and the inner monologuing provided by  Edmondson goes towards establishing her as a fleshed-out, three dimensional protagonist. But it just feels like it’s trying a little too hard to strike that balance that Hawkeye and Captain Marvel achieve so effortlessly, as if Marvel saw the two books’ successes and recruited Edmondson to match it on purpose. It’s still a good little story and engaging despite its problems, but it does feel a smidge manufactured versus the more organic feel those other two books had.

Edmondson goes towards establishing her as a fleshed-out, three dimensional protagonist. But it just feels like it’s trying a little too hard to strike that balance that Hawkeye and Captain Marvel achieve so effortlessly, as if Marvel saw the two books’ successes and recruited Edmondson to match it on purpose. It’s still a good little story and engaging despite its problems, but it does feel a smidge manufactured versus the more organic feel those other two books had.

Taken on its own merits, The Finely Woven Thread is a fine start to another welcome female-led superhero ongoing, and if nothing else it’s definitely nice to see Natasha Romanoff drawn and proportioned as a real human being rather than a curvacious blow-up doll. I like that Phil Noto’s trying something different with artwork, I like that Nathan Edmondson is attempting a different path for the story than the previous Widow runs with Paul Cornell and Marjorie Liu, and I like that dialogue isn’t either completely inappropriate for the tone nor far too ingrained in spy lingo and gritty one-liners. But I still feel like a crucial component I can’t quite put my finger on is absent from Black Widow‘s current makeup, and until subsequent volumes hit that nail on the head I’m going to be left a little wanting.

I definitely recommend reading The Finely Woven Thread at the end of the day, but take it for what it is: a promising beginning that could very easily strike either side of the coin. And it has a guy named Iron Scorpion. Which is honestly a ridiculous name.

STORY: 3.5/5

ARTWORK: 3.5/5

DIALOGUE: 3/5

OVERALL: 10/15

BEST QUOTE: “Home is where the hurt is. That might be the jungle. It might be back on the streets of my birth city. It might be here. And every home has dangerous predators of its own.” – Black Widow